While reading “The Secret Race” this past winter, Josh jokingly emailed me, claiming that Tyler Hamilton and I were essentially the same person. The claim was followed by copied sections of Hamilton’s book, in which he described his constant battle to lose weight.

I haven’t tried the seltzer water and sleeping pill combination, but I could sympathize. Even as the heaviest woman in my immediate family, weight loss never became a life priority until cycling came along. People tell me I “look fine,” but that doesn’t mean much when you want to climb faster, or when everyone you meet tends to look you up and down and ask, “well…have you considered track…?”

Yeah, yeah, yeah I have huge thighs. Thanks for pointing out the obvious.

When I read the book, what hit home wasn’t only Hamilton’s desperate attempts to shed kgs, but his darker moments, too. I am familiar with the depression that can slowly seep into your psyche until, one day, you wake up to realize you’re in the mental health equivalent of no man’s land. There’s a frantic pressure to keep pedaling – whatever’s chasing you isn’t ever too far behind – but you have no idea how much harder you have to go, or for how much longer. Lacking a support system, I don’t get the team car or the race radio murmuring encouragement. There’s only the sound of heaving lungs, the press of insufficient oxygen, and the impending sense that nothing will be enough. I’d scream if I thought it would make a difference, but depression ironically doesn’t allow for that much drama.

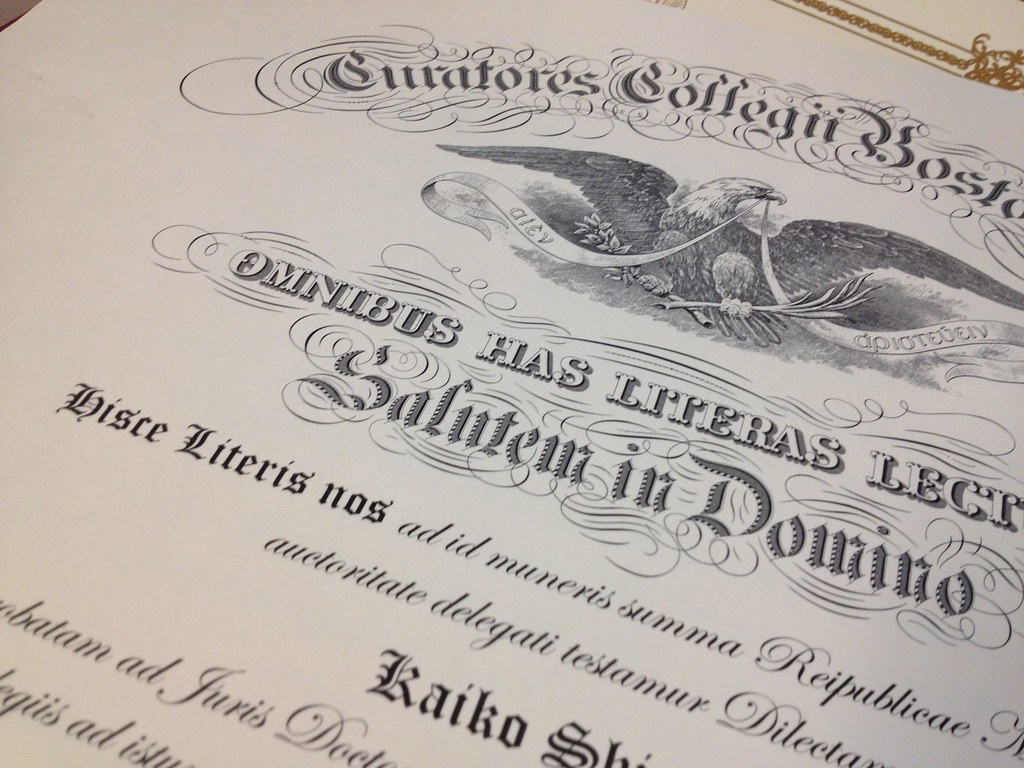

In those moments, my head fills with all the things that I can’t be bothered to think about when I’m happy. That I’m still too fat, too slow, too worthless. That my reluctance to pursue a legal career, despite holding both a law degree and a license, is proof of a complete lack of ambition or life purpose. That, res ipsa loquitor, I am a failure and a disappointment.

And the most recent one, the one that snapped the psyche stretched from a bit too much training and the stress of an upcoming move [and consequently, certain financial ruin], was the declaration that I am “short sighted” for limiting my pool of potential suitors to cyclists.

It was a statement made by a coworker in response to my casual remark that, “well, I only really date cyclists, anyway.” His response stung, mostly because in devaluing what I live and breathe, there was no way to prove him wrong. The disappointing reality is that it is impossible to convince those who lack passion that there is value in being consumed by it. To those in the know, it is probably not surprising that mine has dictated professional decisions, friends, how I spend my money, and people I’d consider dating. To those without obsessive loves, my behavior is foolish and stupid; the equivalent of throwing away life opportunities for a passing phase. The implication being, “well, you’ll eventually grow [up and] out of it, and regret the whole thing, anyway.”

Passions, though, by their nature, become non-negotiable simply due to their Madoff-esque returns on investment. The problem is that, perhaps due to their relative rarity, non-negotiable things can make people uncomfortable. Maybe being careless about a love has become so commonplace that to be resolute about one is seen as pitifully naive. I try not to understand it.

"God, do you know how boring you are? No wonder you have no friends," my sister once interrupted, as I chattered excitedly about bikes.

The declaration was crushing. As a highly functional obsessive In an attempt to be a functional obsessive, I ended up stuffing the most intimate, happy parts of me into a hidden internal drawer. I rarely mention my lifelines: the daily emails and gchats with Josh, pictures from Z from his latest ride up the Dandenongs, tweets from Dave N. about Italian bike trips, Tim and Chan's chorus of exasperated sighs whenever I open my mouth, and emails from A. Without cycling and the friends I've made that share my love - the people who make my life rich and downright fucking extraordinary - I feel as if I'm underwater; everything is muffled and a little hazy. Stay there too long and you can suffocate. The risk of drowning, however, somehow hurts less than getting stabbed in the heart.

"You're starting to listen to these people, and that's scary, Kaiko," Z texted, as we watched Paris-Roubaix in our respective continents.

"Yeah, I know," was all I could lamely type out in response. I knew he was right, but my legs were shot and it was getting harder to keep pedaling. To keep pretending that my life is boring and empty.

The following Monday, I gave that coworker my usual "good morning" and traded polite small talk. I didn't mention cycling, even when he asked what I'd done that past weekend. I tried not to think about how he had fake yawned the last time I'd mentioned a pro race, or a weekend ride, or anything that involved two wheels. I turned down the volume to my abrasively obsessive personality for the rest of the day, and plugged in my earphones for my 8 hour shift of stoic editing.

I lightly smacked the saddle on my mechanical love on arriving home. All my problems were still there, but their corners didn't seem so sharp anymore. I was starving, but couldn't wait to go to sleep, so I could get up to spin those wheels all over again.