A day or two ago, my mother pointed out several tall, skinny trees, their bushy branches peeking up over walls enclosing neighboring yards. Nestled amongst the sturdy green leaves were clusters of small, orange, waxy flowers, almost hidden away, as if self-conscious of their own bland appearance.

“They’re called kinmokusei [Sweet Osmanthus],” my mother said, “those flowers don’t smell like anything up close, but from far away, their fragrance is intense. See? Do you smell that?”

I looked up and sniffed, but didn’t sense much other than my slightly dehydrated throat.

“Uh…no…?”

My mother looked at me as if resigned to the fact that I could actually disappoint her further. “I can’t believe you can’t smell that.”

A ready excuse – that my throat was still chafed from my ride on Sunday – came to mind but hopes of absolving myself dissolved as I realized Sunday was more than 48 hours ago. I tried instead an expression of hopeful expectation mixed with an apologetic one that fell predictably flat as my mother sighed and turned away. I looked for more Sweet Osmanthus trees, resolving to try harder.

To my defense, Sunday’s ride along the infamous Onekan had left me with a slightly sore throat, the product of inhaling too many fumes along the way. My first ride since flying back to Tokyo, I’d successfully persuaded Deej to guide the way while soft-pedaling along to my struggling legs. The opportunity to ride also, quite conveniently, had the effect of forcing myself to attend to my IF, which sat sad and stripped of several crucial parts. Like a neglected child, it lingered silently, waiting eagerly for my withheld love.

It’s not that I intended to put up my road bike for the rest of the year [this is Tokyo, after all, where even the winters are extremely mild at best], or that I was too busy to ride. A half-dismantled bike, however, was easier on the eyes when I spent most of my days staring at the same empty job sites, and giving long, thoughtful hours to my relative ineptitude. A smear of dirt on the underside of my saddle reminded me of New Hampshire, Ride.Studio.Cafe., and a fridge filled with little more than containers of condiments, where I had left a mostly-full, screw-top bottle of Trader Joe’s white wine. What I wouldn’t give, I thought to myself, to be sucking down that amber-colored liquid right now – straight from the bottle – even if “taste” seemed an afterthought to whatever lower grade vineyard bottled the thing.

I was, in effect, “thinking about my life,” as Irvine Welsh once aptly put it in The Acid House, “and that is always a very, very stupid thing to do.” Realizing the futility of walking the same desperate mental circles, I pulled my head out of my own ass for five seconds to beg Deej for a ride. It worked. We planned on hitting the rollers along Onekan early Sunday morning.

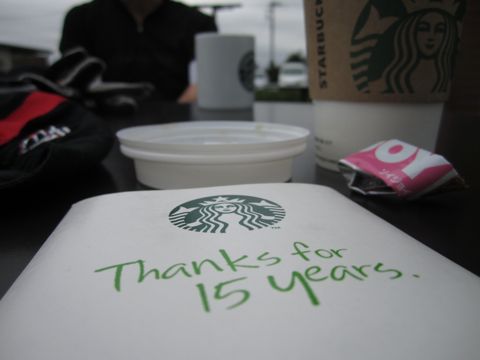

A relatively short loop, it’s a quick out-[to-a-Starbucks]-and-back type route, conveniently located just across the Tama River. When Deej told me it was mostly rollers, I expected something more like Boston routes, where there are flat sections punctuated by small hills. The Onekan, though, feels more like riding a series of hills until the last mile or so, where the combination of no lights and flatter ground make ideal conditions for a dead-on TT sprint. The hills won’t kill you, but they’re challenging enough when, like me, you’ve gone weak in the legs and soft in the middle.

And given that a veteran Tokyo cyclist who loves to climb was guiding the way, we inevitably hit a back road off the Onekan. The grade surprisingly steep, we picked our way up the road on the sidewalk while cars aggressively sped past us. The sidewalk less than two feet wide, crowded on either side by intrusive telephone poles and hedges, I realized that spinning in the saddle wasn’t a prudent option as the uneven asphalt – punctuated by tree roots – made my butt bounce against my saddle. I stood up and spun, almost got hit by a car when we were back on the road, then slogged the rest of the way back to the Onekan.

Our flavor of Paris-Roubaix behind us for the day, and never one to chase or race, I established a steady pace on the way back, letting other cyclists slip past undisturbed. But the Onekan presents enough competitive opportunity to keep things interesting, and when a slight woman on a carbon fiber whatever, in Assos shorts and Lightweight wheels, bringing up the tail end of a paceline spun by, a prickle of ambition coursed through me. By the time we drew up behind her, I was secretly frothing at the mouth to go, my wheel dangerously overlapping Deej’s. He looked behind at me, I nodded, and we pushed up, over, and past. I felt briefly like an asshole, but that didn’t keep me from patting myself on the back just a little.

I remembered that cathartic surge forwards again when I finally smelled those Sweet Osmanthus flowers. My mother was right, they’re hard to miss; their thick scent permeating the air like the heavy perfume of an overbearing female relative. I looked up at those ordinary flowers – one might go so far as to call them unattractive – and found again that lost realization that appearances never quite matter. That that huge piece of paper I got from Boston College Law – however impressive with Latin words all over it – probably shouldn’t saddle me with daily existential crises.

And that although I may be the only person in Tokyo with black Sidis, that I might have a small, tiny measure of something in my legs, too.