It was 6 a.m. on a Monday morning and I was converting kilometers into miles and meters into feet. I wasn’t doing this two hours before I was supposed to leave for the same planned ride because I ran out of time the night before. I still had water bottles to clean, a chain to lube, and tires to pump. I hadn’t eaten breakfast yet. But decades of [sometimes forced] socialization have taught me to err on the side of being slightly unprepared and more than a little disorganized. I’m not particularly proud of this. When friends teased a law school classmate about color-coordinating her bills and arranging her pantry items alphabetically, I felt a deep envy and leaned in to ask her questions, like if diced tomatoes are placed under “D” or the more standard “T,” instead of slowly disengaging myself from the conversation and backing away. But take a few bar exams and hang out with some normal people, and the ability to shrug in the face of unexpected life events turns into a valuable life skill. Or so I like to tell myself.

Unfortunately, being unprepared for a hard ride is entirely different from, say, being late to a gathering that involves fashionable clothing and/or alcohol. Contrary to what my parents have taught me, you’re allowed to show up at least 15 minutes late to most life events as long as you look appropriately disheveled and fabulous. Even those cutesy, cliché excuses – “Sorry, I had to wash my hair,” – are acceptable, if it’s paired with some the right Louboutins. You’re practically expected to be late; so much so that I’ve made the conscious decision [yes, more than once] to finish watching the Law & Order episode I wasn’t paying attention to until I brushed on my mascara and decided that finding out who killed the wannabe-model-turned-high-class-escort would probably enrich my life for the better. If it’s an episode I’ve seen before, I figure the familiar “doink-doink” will facilitate choosing between the dress half-zipped up around my waist, the jeans on my bed, or the skirt I’m holding in my hand. Usually a bit of guilt kicks in right when the story takes a twist, pointing the detectives to the brother of the boyfriend-suspect, and I clatter out in my best heels. Or I switch them out for flats, change the pants for a skirt, decide that other jacket is better, and arrive later than if I’d watched the entire L&O show, but still relatively early by Friday night standards.

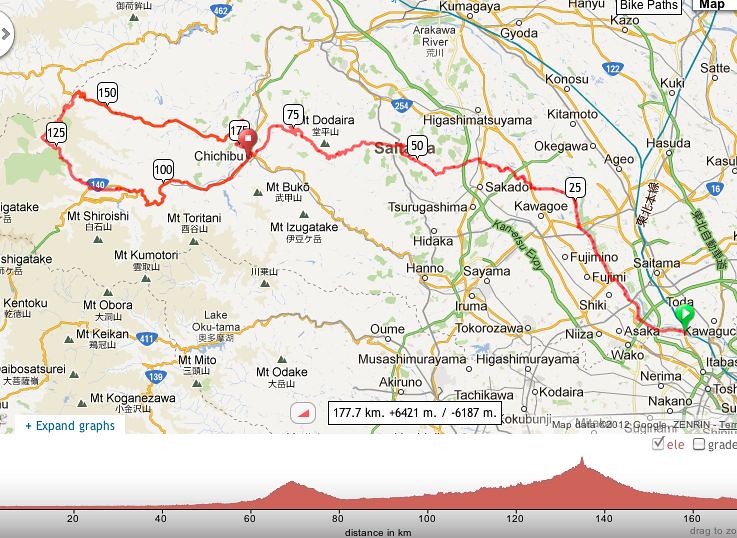

But if a ride either 1. involves more then two people [yourself included], or 2. is a charity ride gifted to you by a stronger cyclist who has a natural ability to lie to your face or has some misplaced confidence in your abilities as a cyclist, there’s a measure of personal responsibility required that isn’t forgiven with an “oops,” and a tipsy giggle into a cocktail. Avoiding situations where that “oops,” turns into a hoarse gasp and the tipsy giggle into something similar to dry heaves, situations in which you embarrass yourself to the point where people become embarrassed for you, demands some cruel self-awareness. On this particular Monday morning, my belated, half-assed version of looking over a ride route defined self-awareness as 3622 feet of climbing. In 30 miles.

“That’s...hilarious,” I said to the computer screen, while I typed a frantic email to Deej.

“See you soon,” he mercilessly replied.

I remembered then the first time I climbed Otarumi pass, the first climb on the route. It was scorching hot, and I spent most of the time staring at my sweaty forearms, wasting hope on some chance that the climb might end at the next corner, or the one after that, or definitely at the upcoming bend. I had thought it was hard. Hard enough that I hadn’t had the courage to go back. And now I was staring at a route that made Otarumi look as flat as I am, while Bijoudani and Wada bloomed ahead like a Victoria’s Secret model. I had done almost double the climbing courtesy of another David, last July, but spaced over four times the distance. Suddenly, staying in bed on a cool, clear day with Book 2 of the “Game of Thrones” series had an obvious appeal. But I had agreed to do the ride. I packed up my bike, portaged it onto a train, and met Deej at Takao station.

Our first ride together in months, we kept a conversational pace, trading titles of good books recently read and ride routes visited. We were already starting the climb up Otarumi and I kept waiting to run out of breath, gears, and hope. Deej chatted away, and though it seemed imprudent to waste energy, I continued to reply in full sentences, half-bracing myself for the pain that was surely waiting for me at the next corner.

“Oh, see, we’re done with Otarumi,” Deej said, mid-conversation, pointing up at the bridge overhead that marked the end of the pass. It barely registered before I was clutching at my brakes, trying to descend and not die at the same time.

Then we swept into a smaller, rougher road, spun up a few steep, short grades, and dismounted to walk around a gate that warned of wild boars and closed the path to cars. The asphalt was uneven and littered with pine needles and large rocks. The fresh remains of mini landslides welcomed us within the first few yards but Bijoudani pass was otherwise deserted. Not even a wild boar in sight. We climbed, and climbed and climbed some more. I remember the conversation became decidedly one-sided as we ascended, my replies becoming first broken, then reduced to breathless one word answers. I choked out a “how much longer?” at one point, those three words stealing precious oxygen from my lungs. Deej, meanwhile, was fully functional, talking in complete sentences and documenting my lone suffering via camera phone.

At the top, we were less than 15 miles in, and I dove into a Clif bar. I would polish off two by the end of the ride; my most gluttonous 30 miles to date.

Rocks and large branches slowed our descent down Bijoudani, until we reached smoother asphalt and something like a 18% grade. We saw our first cyclist of the day there, throwing himself up the slope. I looked at him with a mix of pity and awe as I passed by, my forearms aching from squeezing brakes that seemed largely ineffectual. I couldn’t wait until the road evened out.

But when it did, my legs seemed shot. Deej’s wheel – spinning easy – got smaller and smaller. Frustrated, I shoved my weight back on my pedals, tried to lift my knees faster, but with little success. I made the mistake of looking down at my cycloputer, the face mocking me with the stunning speed of 13.4mph. Mentally sighing, I resigned myself to the inevitable: I was going to put a foot down on Wada pass.

Depending on who is being consulted, Wada pass, much like pot, is either a gateway drug that builds up a dangerous addiction to larger mountains, or is sufficient by itself to keep one coming back, for one more hit. The climb [when approached from the easier, west side] features two pitches of 12%; one short and sweet near the middle of the climb, the other unforgivingly at the very end of the pass. “If people put a foot down, it’s usually at the end of that first pitch,” Deej had said, adding in along our route all the places where a “chubby” friend had clipped out. This information kept my feet glued securely to my pedals, my unique blend of stupid pride adding to my stubbornness. The façade, however, crumbled after Bijoudani. It chafed, like a solid hit of high quality pot, but once it went down, less than I expected. That rare voice of praise quietly told me I had bagged a substantial peak, given my lack of experience climbing anything over 1.25 miles with 6+% average grades. It seemed to pat me on the back for a job well done. “You tried, you did your best,” it said, “it’s okay, you’ll do better next time.”

I will admit that I am not beneath social or intellectual sandbagging. There can be an egotistical utility in briefly associating with people who can’t spell or who lack common sense, however basely acquired. In desperate times, the correct use of “your” and “you’re” can assuage an ego battered by underemployment. Yet, at the end of the day, it’s cheap. I know there is no point to pride derived from the ability to do what is a given, a grammatical standard that most literate people are capable of fulfilling.

That doesn’t mean the idea of putting a foot down wasn’t tempting. It was. As the number of places my toe touched the ground increased, the lower I would set the bar, and consequently, I would be gifting myself more room for improvement. But Wada pass, unlike Bijoudani, offered two or three places flat enough to coast for two or three seconds. The brief reprieve was inexplicably sweet, and the smoother, debris-free asphalt somehow made the climb a little more tolerable.

Deej kept me distracted, talking about something to which I could only utter, “uh huh…uh huh….okay…” He would occasionally disappear to sprint up a part of the climb, then double back to resume conversing with my huffing and puffing. Halfway up the last 12% section, a whisper of a suggestion of doubt invaded my mental stranglehold. I attempted to beat it back with equal parts anger and self-derision. It usually works. It almost didn’t.

We turned a corner as my fury peaked, and there ahead of us, a mere 100 meters away, was the gate signaling the end of the climb. I spun faster and wobbled to a stop at the rest area beyond the gate, the hard clack of disengaging cleat from pedal sounding close to treasonous after the collective effort of refusing to yield. I dumped myself onto a bench to breathe for the next 20 minutes.

After a descent down steep, narrow, twisting roads, the road leveled out. Deej kept the pace well above 17mph, a pace I might not have voluntarily chosen after climbing three passes, but sitting on his wheel was more appealing than struggling alone at a slower pace. A final hill – no more challenging than the rollers on my usual ride route – nearly ripped my legs off. Glutes, thighs, and hip flexors seared to the point of becoming momentarily numb until the blood rushed back into muscles. Then they screamed.

Elderly hikers plodding along the road signaled the end was near. A left turn, then we were back at our meeting place. We said our goodbyes – Deej was late, and I miraculously alive – promising to meet up soon for another ride. I clomped back into the train station, packed up my bike, grabbed a rice ball and inhaled it on the way home.

By the time the train pulled into my train station, I was fully cracked. Glassy-eyed, covered in damp sweat, I hauled my bike up another flight of stairs, and somehow gathered enough mental strength to focus on putting my front wheel back on. I was useless for the rest of the day, and sore enough the day after.

But like any good ride route, I’ve been planning my return to those passes since. It’s a good training ride, I’ve heard, for bigger, steeper, longer climbs. A place to build up the legs and stamina for the stuff with double-digit average grades. A gateway ride to hardcore.