“Oh but see, she’s dressed normally.”

It was a snippet of a conversation that I caught as I rode by two guys last Sunday morning, who were apparently discussing what cyclists wear. I guess I am dressed normally, I thought, as I shifted the overstuffed Baileyworks messenger bag on my shoulder layered over a t-shirt, a zip up hoodie, and jeans.

But then again, the next thought came somewhat slowly, it is 3:15 a.m. on a Sunday morning.

In twenty minutes, I would turn onto a still-dark street and meet a few teammates for the first time, before helping to load up a rented van with all of our respective bikes. 3:35 a.m. on Sunday morning [or is it still Saturday night?] will very rarely be an optimal time to be making introductions, but approximately three weeks ago, I had decided it would be a good idea to register for a race. It seemed like the thing to do when you join a race team.

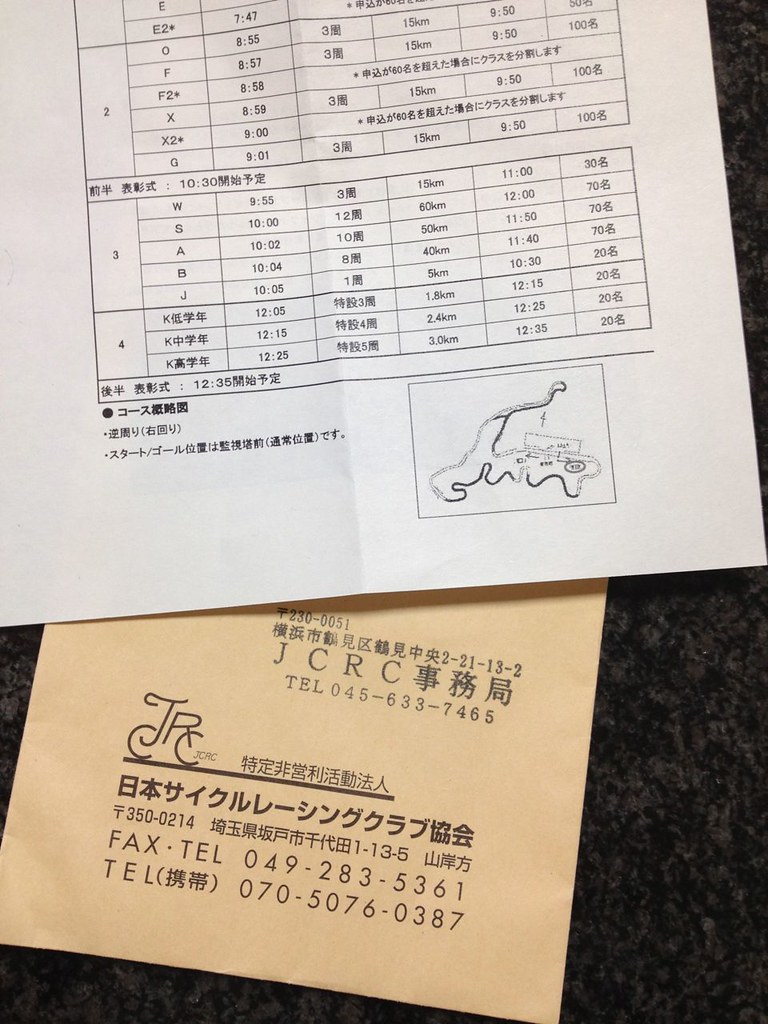

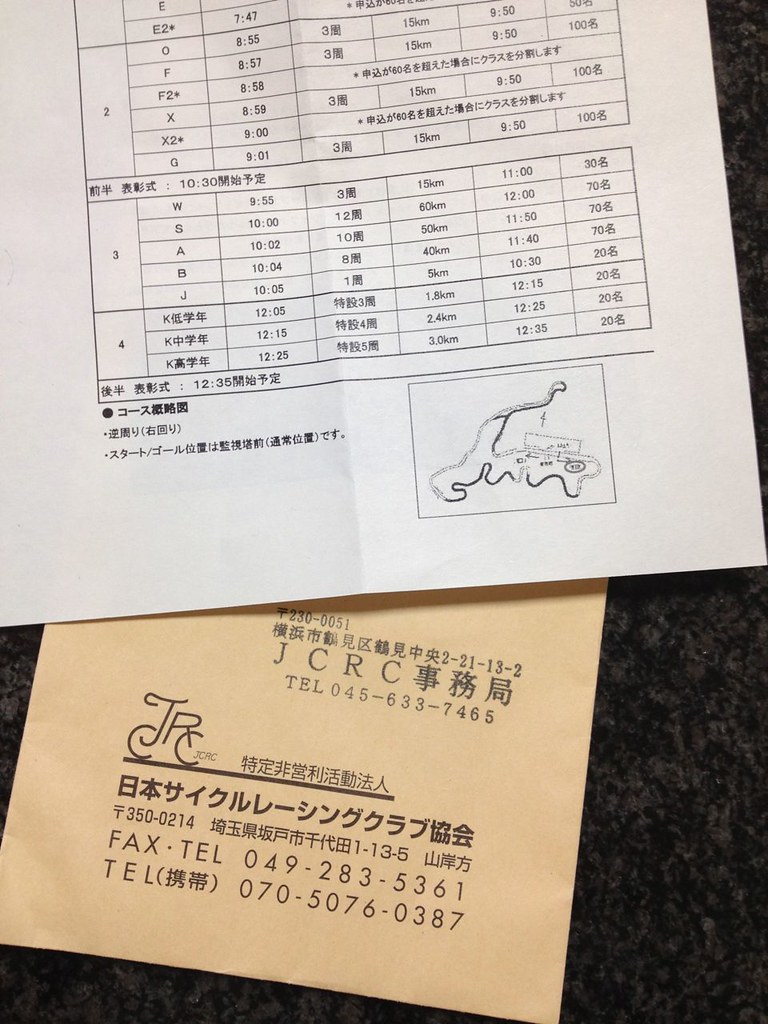

I was, however, somewhat limited in my options for races. It was like being forced to choose a date from a drug rehab center: there were plenty of skinny heroin addicts [hill climbs], and a handful of meth heads [enduros], but given those options, I went with the guy that looked like he had just made a few bad decisions, had snorted a few too many lines of coke. Approachable and seemingly normal; a June crit organized by the Japanese Cycle Racing Club [JCRC] at the Shuzenji circuit in Izu.

It was probably a good thing that I had no idea what I was getting into. Reliable sources told me that the race was hilly, but since we would be racing clockwise [the “reverse” way], there would be three climbs of around 5% each, per 5km lap, instead of the 8-11% pitches if you did it the “right” way. No flat ground, just climbs and descents. But how bad could 15km be?

“Oh, yeah, and,” Eric added, when I met him for some intervals around the palace early one morning, “there’s a hairpin turn, too, plus kind of a corkscrew after that.”

I paled. I was quickly finding out exactly how unsavory my June date would be. But loathe to retract my intention to race, I registered anyway. We were already on the highway when I learned that the last climb to the finish line was more like 10% rather than my anticipated 5%. I almost jumped out of the speeding van. “I don’t want to waste any of your time,” I wanted to say, “really, just let me go home so I don’t embarrass any of you any more than is absolutely necessary.” Instead, I tried not to hyperventilate as I watched the sun come up on a Sunday morning from the back of a van packed with carbon wheels, race-ready frames, overstuffed backpacks and one lone steel bike.

Less than two hours later, we pulled up to the circuit. Located in Shizuoka prefecture, Shuzenji Cycle Sports Center is a multi-facility bike park with a top-class mountain bike course, a small dirt bike course, a 5 km circuit, and an indoor velodrome that serves as the training ground for a pro keirin school. Between the entrance to the park and the circuit, there’s even a mini rollercoaster and a carousel for the kids. Arriving before the gates opened, we all trekked to the bathroom to change into our kits, and for possibly the first time in my life, there was no snaking line outside the women’s room, although the men were all forced to line up outside.

Dressed and ready, we were sent to pick up our numbered helmet covers and sensor chips, and in reconning the course, I realized exactly how hard this was going to be. “Murderous,” was the first word that came to mind, followed by the phrase, “I am fucked,” as I realized that this was going to require a lot of shifting. In the front. Suddenly those seemingly unnecessary repeats of hills-that-are-probably-longer-than-any-climb-at-Shuzenji became almost useful, but useless because I clearly hadn’t done enough of them.

I marinated on this newly-gained knowledge of my first crit course as I watched and cheered on Mr. Yoshimura, Mr. Yamanoha, and Mr. Fujimaki race in their respective classes. Mr. Ishizuka showed up too, after riding the entire way from Tokyo to watch us race. Too soon it was 9:55 a.m., and I was lined up at the start line with seven other women. We started out as a group up the first climb, but I made the mistake of riding my brake through the descending turns, losing time. By the last 10% pitch, I was pulling up the rear and just about dropped when the girl a few feet in front of me dropped her chain. A courteous girl [“Oh, excuse me! Sorry!” she squeaked as I almost crashed into her] with thighs the size of my calves and Di2, I Contador-ed her and pulled myself up the climb as fast as my burning legs could turn over the pedals. Two more laps to go and I stuck my bike onto the next girl’s rear wheel.

By this point, the faster women were a good three minutes ahead, while the rest of the field had shattered. I passed two more women on the next climb and rode the rest of the race in the lonely, demotivating hell that is no man’s land. I was trying to climb faster than 8mph when Mr. Yoshida, racing in the top S class which started five minutes behind the women’s field, passed by in a small group of pink helmet covers.

“Kaiko. Keep going,” he said.

By the third lap, my lips were quivering from exertion but I stopped riding my brake on the descents. I managed to climb the last incline standing but still fumbled to the finish line in my little ring. “Fifth! You came in fifth!,” my new teammates told me. “Oh,” was the most I could manage, afraid that if I said anymore, I would start dry heaving. I sat in the grass for the next 20 minutes, feeling nauseous and regretting every swallow of iced tea as Mr. Yoshida went around and around and around. We shouted and clapped every time he passed us, until, twelve laps later, he vanquished our team by coming in third.

An hour and a half later, I collected a certificate for coming in within the top 6, and posed for a few awkward photos. We all snapped shots of Mr. Yoshida’s third place finish before packing our bikes back into the van for the trek home. A few hours [with a tongue lashing for general incompetence] later, we were back at the shop. Exhausted, sweaty, and running on fumes, even as we cradled still-fresh disappointment, we were already talking about next time.

I woke up yesterday with cranky muscles and sunburn. But between the rewriting, editing, and proofreading, I stared out of my office building window, counting the weeks remaining, and intervals necessary, for July.