Therapy, counseling, treatment. Call it what you will, as the basic idea stays the same: an admission that somewhere along the way, something ceased working properly, placing you in a chair or couch, pouring out emotions you usually wouldn’t in front of a stranger. Though not yet fortunate enough to be able to afford the kind of therapist that owns [what I have convinced myself must be] a comfortable couch, I’m a veteran of sobbing in front of strangers within minutes of meeting them.

“I...I just...I’m just...” The tears start to dribble and leak out of my eyes, gravity threatening to pull liquid snot from my nostrils in thin ropes onto my lap. Horrified anew at my own frail grasp on mental clarity, sanity, and lack of crying etiquette, I apologize. “I’m sorry,” I say to someone who I am fully aware is professionally bound to pretend to care about the petty problems that I claim are swallowing my life. I say this as I liberally help myself to their tissues without asking, as if those two flimsy words, overused by assholes everywhere, could possibly redeem me.

The paradox of therapy, I have learned, is not that everyone goes [therefore rendering the implication that therapy is only for the psychologically broken or askew, moot], but that it makes one prone to paranoia, thus creating a set up for more therapy. It starts at the reception area, where I wonder whether there’s some hidden test in which magazine I might pick up from the coffee table. Am I superficial and inclined towards eating disorders if I pick up the trashy fashion magazine? Left-wing intellectual if I pick up the New York Times? Where does this local business magazine fall on this imaginary mental scale? Instead I choose to twist the scarf in my lap, trying to act comfortable with bored isolation. People stare out into space all the time when there’s a perfectly entertaining issue of The Economist lying within 2 feet of them, I tell myself, because by this point it’s too late to get up and pick up the magazine. The therapist might be out any minute, and no one wants to get caught in that moment after a reading choice has been made only to have to put it down before you can sit down again. It makes the person picking up the publication feel awkward, and [presumably] the therapist feel guilty for being on time. So the time between arrival and appointment is stared down in an affected blasé demeanor, while I try not to focus on how crazy my therapist will think I am this time.

This incessant back and forth - the mental pendulum that swoops and swings between worrying about what my therapist thinks of me and reassuring myself that she’s voluntarily chosen her profession and thus proximity to individuals like me - is characteristic of the paradox of therapy. Much like the misleading label of “therapy” itself, which implies some goal or end point. To anyone with a fully functioning head on their shoulders, the assumption that a remedy for a loopy mind would follow any sort of linear path is probably irrational. To those with impaired psyches, however, it makes perfect, illogical sense: pay for enough professional cry-fests and eventually enlightenment in the form of emotional stability, balance, and resilience will ensue. Or so goes the uncharacteristically optimistic hope.

And though my brain might not be wired right [then again, whose is?], it’s not so abnormal to hope that a linear progression towards a defined goal can actually exist in life. There seems to be a fairly steady increase in exhibited bitchiness right before I get my period; why couldn’t the same type of escalating growth apply to other, more appealing aspects of my life? I’ve been told the same can be said for riding a bicycle: do it enough times and you’ll improve. Maybe just a little bit, but enough to plot the beginning of an upward linear vector.

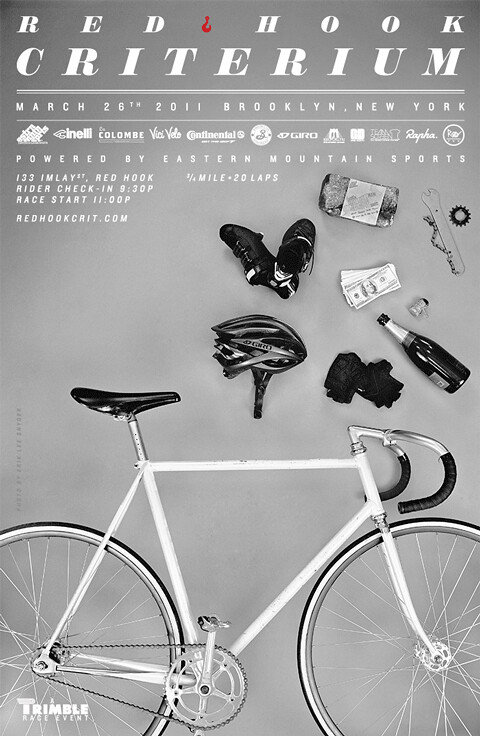

But if the state of my mental health mirrors my ability on a bike, improvement has remained either elusive, invisible, or both. My frustration is apparent enough to my therapist [what did I do? How did she know?] who continues to tell me to give myself a break once in a while. It’s reassuring to hear, but like most things in therapy, it also gives rise to the opposite sentiment of extreme stress. Breaks sound nice, but without a fire under my ass to keep me perpetually on my toes, I fear that I’ll ultimately lose something I love dearly. That I’ll somehow forget how to get dressed to head out for a ride. I’ll take it easy this month, I might convince myself, as my bicycles gather dust. Or I’ll turn around at the base of a hill telling lying to myself that I’ll do it tomorrow, or next time, for sure. Mental balance might be nice when it comes to the rest of my life, but it hints at staying a terrible cyclist.

For that reason, I was rolling away a few days ago, before anyone should really be awake, much less on the rollers. No sprinting, just rolling easy, but struggling nonetheless. Maybe this isn’t enough, I thought momentarily even as my empty stomach churned in protest. No, but it is, the other side of my schizophrenic brain reassured me, because who in their right mind voluntarily rides rollers before work, with only a cup of coffee to fuel them? The mental battle fizzled away slowly as the loss of sensation in my butt turned to sharp pain, but whispers of it came back later. And I know it’s going to, even when bright sun and the outdoors can snatch my attention away from a pair of paradoxically weak yet heavy legs.

But in a way, I take solace in the swinging between extremes of which I am expert, be it in therapy or riding. It’s an uncomfortable ride, sometimes prone to motion sickness and emotional instability, but the motion of sweeping from one end of the spectrum to the other also sends me through, however briefly, a middle ground. That perfect point between failing and succeeding, when nothing is felt but maybe a dose of sun and a wisp of wind, when the asphalt seems to both melt away and hold you up. In those short moments, I switch to my big ring and let out my inner Tatianna Guderzo; my version of throwing rocks at Schrödinger’s cat.